November 26-December 2, 2023

Snow at Last!

A week of gray, dreary days ended in a splash—with skies breaking open and sunlight bathing our first big snowfall of the year.

Week in Review

Despite the notable lack of snow, we have definitely crossed the threshold from glorious fall into the depths of winter, and everything has been looking really gray, brown, and dead lately.

But, then we ended the week with a new blanket of sparkling white snow, and it's like a sigh of relief. This is what winter is all about!

Now the world feels alive and vibrant again, there are fresh tracks to follow, birds congregating at the feeder, and glints of sunlight shining through icy crystals! I'm thrilled because the timing is perfect for my winter ecology talk this afternoon at the Winthrop Library!

With the leading edge of winter upon us, we've been getting a mix of newly arriving winter birds alongside some fascinating late migrants. Our mini-invasion of pine grosbeaks is still going on, though perhaps in smaller numbers, and sharp-eyed birdwatchers have also picked up on a couple common redpolls at Pearrygin Lake.

Pine grosbeaks and redpolls are both finches in the Fringillidae family, and these birds are notorious for staging large-scale movements called "irruptions" in respond to cold temperatures and diminished food supplies.

Other interesting birds have been a trio of sea ducks hanging out on some of our larger lakes. There has been a red-breasted grebe at Pearrygin Lake, plus at least one white-winged scoter, and one long-tailed duck, at Big Twin Lake.

All three of these birds breed on arctic tundra in northern Canada and Alaska, then spend their winters along the coasts of North America. The Methow Valley is not their typical habitat, but it's possible that some stop briefly in the Valley while traveling to the ocean.

Scoters are notable because they are scarce, hard to find even where expected, and their populations seem to be declining. And the long-tailed duck is a special sighting because they seldom venture south of Canada on the Pacific Coast. Finding unusual birds like this make any outing in the Methow Valley a memorable experience!

Observation of the Week: Snow and Ice Crystals

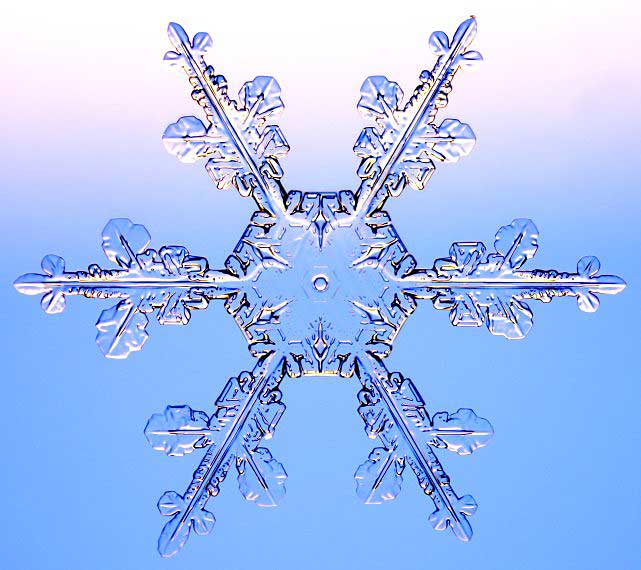

There's a lot to say about snow, and I'll be covering this topic in my talk at the library today, but we can start by appreciating the beauty of snow and ice crystals.

Snowflakes are produced high in the atmosphere, as supercooled clouds at -40 degrees convert water vapor into ice crystals. Each snowflake grows around a single, tiny particle floating in the atmosphere. These particles include things like dust, soot, pollen, and spores.

The nature of hydrogen and oxygen bonds results in an immense variety of fantastic, six-sided geometric forms that we recognize as the classic snowflake shape.

But as soon as these fantastic shape form, they begin breaking down, first by colliding with each other and being buffeted by the wind, and then by piling up on the ground.

Alongside external forces, snowflakes also begin to self-destruct as water molecules at the highest points of the snowflake begin moving to the lowest points. This gradually transforms sharply pointed snowflakes into rounded pellets that stick together to create the dense snowbanks that animals are able to live in and human ski on.