June 23-29, 2024

Can you feel the call of the mountains?

This is certainly continuing to be a very strange spring-summer season, with more cloudy days, and one of the biggest rainstorms of the last couple years, alongside a few days of high temperatures.

Week in Review

It's all too easy to spend days puttering around the yard, taking care of our chores and errands, while completely forgetting that there's a glorious world unfolding in the high mountains at this very moment.

I was lucky enough to make it up to Harts Pass yesterday (my first mountain outing this year!) and be reminded how truly special these mountains are. Yes, it would be challenging to do any extended hiking because there are still plenty of snowfields, but the flowers are just starting to get exciting, and many birds are singing.

After a long, heavy rain, I figured it would be a good time to drive around looking for amphibians and other critters awakened by the moisture. I went out one night after the rains ended and found a spadefoot toad. These toads spend the dry summer hiding in underground burrows, but as soon as they feel/hear a steady drumbeat of raindrops on the ground they emerge to mate or find food.

Driving up Lester Road, and at Campbell Lake, I was also amazed to spot at least a dozen common poorwills, the most I've seen in a single night in my life. These small nocturnal birds, cousins to the common nighthawks we see flying high overhead at sunset, love to sit on dirt roads. They're incredibly well hidden, but you can't miss their intense orange eyeshine in your headlights.

Otherwise, things keep humming along in the valley. Nearly all of our birds are busy with some part of raising babies or starting a second nest. At our house, we have three pairs of swallows with new nests in our yard right now, while other swallows and bluebirds finished their first nesting efforts 1-2 weeks ago. Yesterday, I also noticed 22 crows flying around in a big noisy group. This was almost certainly a gang of teenage thugs, freshly independent from their parents and having the times of their lives.

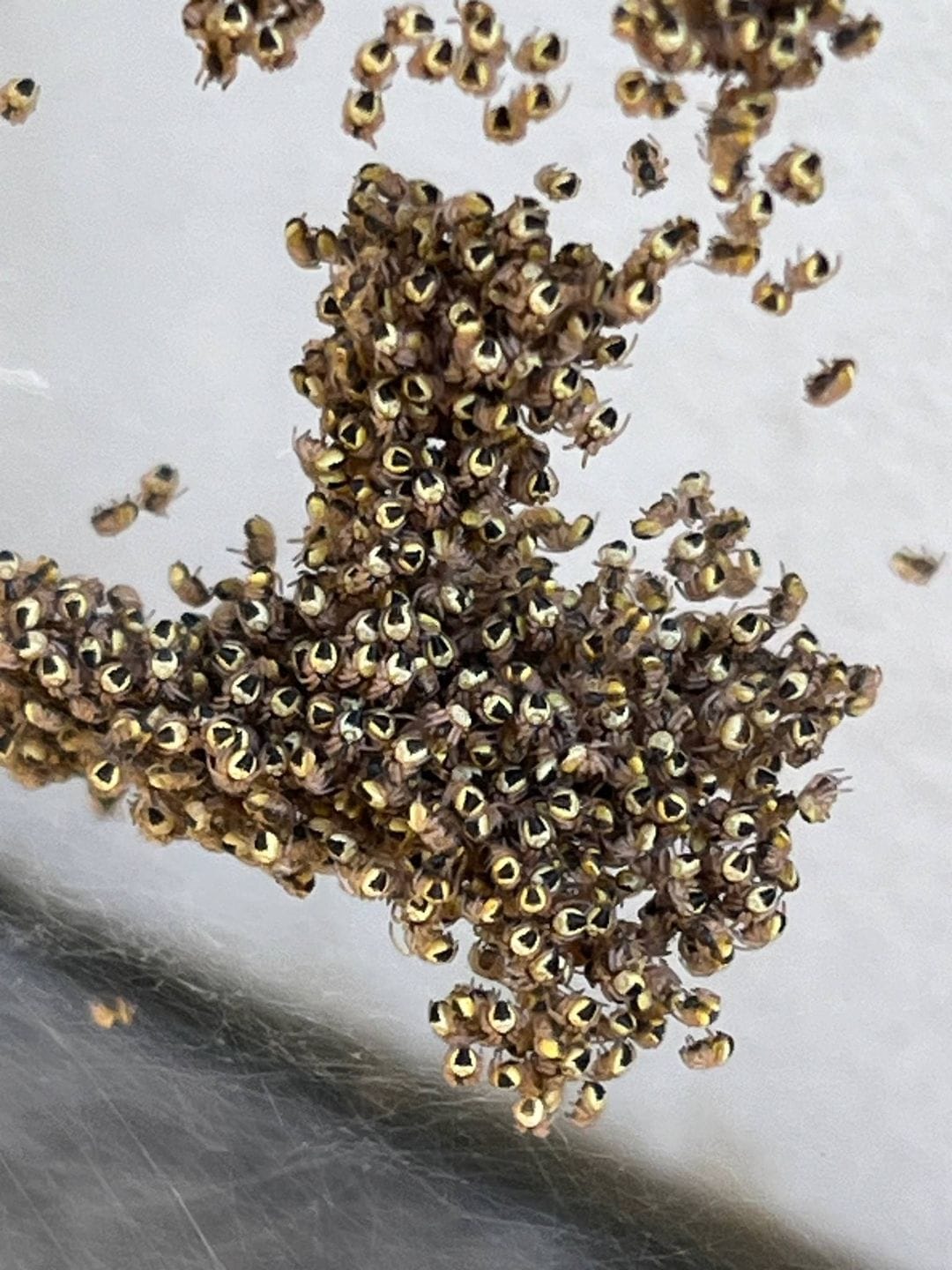

Birds aren't the only animals with babies, several people have posted photos of baby spiders on the Facebook group. Dozens to hundreds of spider eggs develop inside a silk cocoon (often over the winter), then all the babies hatch at once. At first, these babies cluster tightly together as they continue to digest the yolk stored in their abdomens, but then they quickly begin dispersing when their yolk runs out and they start eating each other.

Finally, our only notable mammal sighting this week was a bull moose with a new rack of velvet-covered antlers. We think of deer having velvet antlers because we see them frequently, but it's easy to forget that moose have these too.

Observation of the Week: Water Smartweed

You may have noticed conspicuous, pink, thumb-like flowers around the edges of some of our lakes. These are the flowers of an interesting plant called water smartweed (Polygonum amphibia), which has the fascinating ability to grow on either land or water.

Though these plants produce flowers, nectar, and pollen, they are far more likely to spread from their easily broken stems or by cloning themselves. Strong winds and waves, as well as grazing cows, produce large numbers of fragments that readily take root wherever they end up.

A single one-inch fragment can grow as much as forty feet per year, quickly turning into one huge colony that can theoretically stretch for miles along a shoreline or cover many acres of open water.

All this productivity is almost certainly a net positive. In many wetland habitats, smartweeds end up being the only, or the most prolific, flowers available for pollinators. At the same time, the plants produce phenomenal amounts of nutrients and organic debris that fuel aquatic food webs.