February 23-March 1, 2025

So many changes in one week!

This was a week of sudden transformations as the sun came out, temperatures soared, and the snow started to melt.

Week in Review

This week has been so busy I don't think I can fit all the observations into one post! Birds are singing and calling everywhere now, and our first migrating bird, the Say's phoebe, has just arrived (first seen on February 26)!

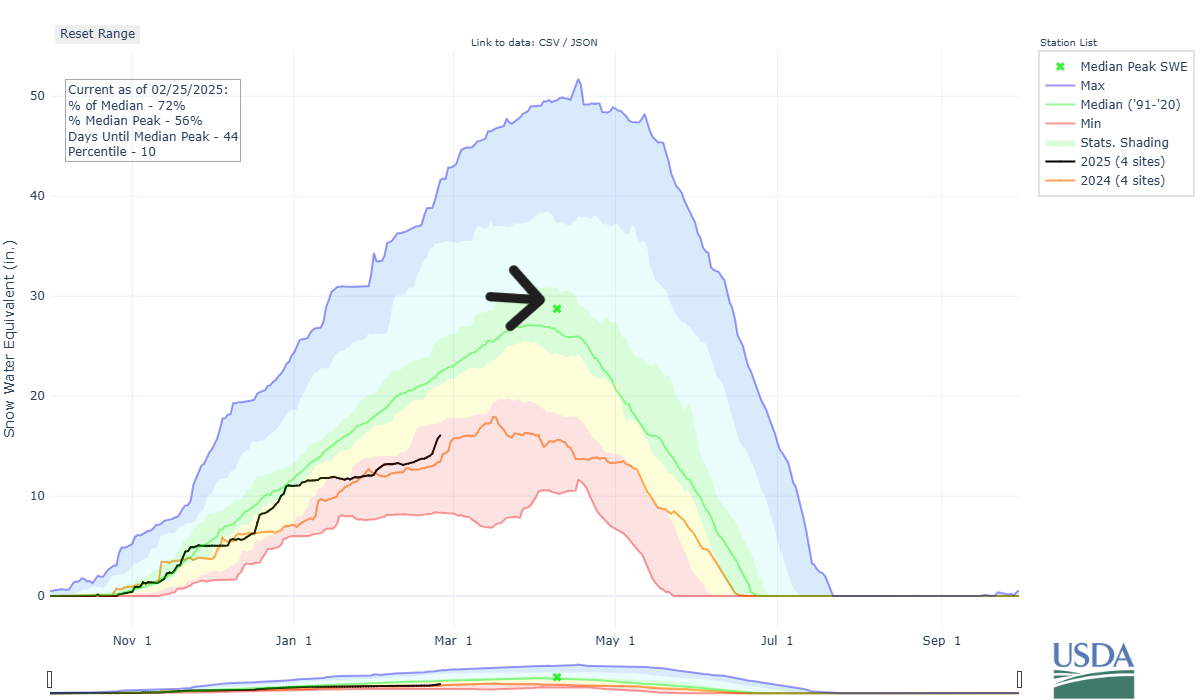

After a long, cold winter it's exciting to observe these welcome changes and I'm super excited for the coming spring, but I'd be remiss if I didn't add one sobering note. Our snowpack, and the amount of water in our watershed, is perilously low. We started the winter with significant amounts of rain along with heavy snowfall that put us at 80% of average. But then things tapered off, and sadly it doesn't bode well for the coming year.

This is an odd and fickle mix of conditions and expectations, but these are also typical spring conditions; after all, it is famously said that "April is the cruelest month." For example, on February 19 I heard a lone red-winged blackbird singing by itself, and within days a large group was gathering and loudly singing. This is a sign of the coming thaw, but a day later this same group of birds struggled to maintain their spirits in a driving snowstorm!

These blackbirds are driven by the need to work out their dominance hierarchies, find mates, and establish ownership of fiercely contested territories in one of the valley's limited patches of cattails. The water may still be frozen, and the plants dried up, but on sunny days the birds are already staking out their claims.

Other changes include the arrival of American robins and European starlings, both of whom find much of their food on the ground and can only survive if there are enough open patches to feed on. I also noticed my first big group of Oregon juncos passing through the yard, which indicates that they're either starting to arrive or else restlessly moving around the valley from locations where they'd hunkered down for the winter.

Perhaps more surprising were the three killdeer standing on the ice at Pearrygin Lake on February 28. Killdeer are hardy, early-arriving birds, but it's hard to imagine what food they're finding to eat on the ice!

The answer might come in the form of early-emerging insects that end up too cold to fly and become trapped on the snow. And a significant uptick in insect activity can be measured in the midges I first noticed last week. Starting with one small group, this same group is now 3x larger and there are multiple groups around the yard.

Finally, it's heartwarming to see a handful of birds starting to check out the nestboxes because everything feels right once birds start singing and feeding hungry babies in their nests again. So far, the most active birds have been a pair of house sparrows. These are fascinating birds because they are an introduced species that is slowly becoming native to North America, and one of these days I'll tell their story in a newsletter.

Observation of the Week: Killer Trails

One observation this week underscored the paradox of our ski trails. I'm not criticizing these trails but at the same time there's a lot of pressure to create more trails yet we seldom highlight the more obscure consequences of these trails.

Last week I wrote about springtails, which are a vital animal in our forest ecosystems. They are always here, but they are most noticeable in late winter. This is when the snow starts to melt and release nutrients trapped in frozen ice crystals, and this is when countless springtails migrate to breeding patches.

Last week I included a photo of a large number of springtails, but I hadn't noticed that they appeared to be on a ski trail until I observed this same phenomenon on a ski trail myself. It immediately became clear to me that these incredibly small animals were being concentrated, and almost trapped, in the sunken groomed ski tracks. I made a rough estimate of how many springtails I saw in one foot of ski trail and calculated that I was killing or maiming around one million springtails in the course of a single short ski outing. At the same time, I noticed that the springtails were most concentrated along particular stretches of trails and it made me wonder if this is where ski trails were cutting across traditional "migration" routes to their breeding areas?

However, this isn't the only impact of snow trails. Two weeks ago I posted a photo of a vole on the snow and mentioned how voles (and countless other small mammals) survive entirely in the subnivean zone. The subnivean zone is an empty space that forms between the ground and the overlying snowpack, and this space is critical for the survival of small mammals because it allows them to construct elaborate webs of tunnels (like subway systems) where they can hide from predators and find food.

However, when we snowmobile on the snow or groom ski trails, the weight of our machines collapses the subnivean zone, cutting off travel routes for animals under the snow. As a consequence, small mammals that need to reach their nests or stored food are forced onto the surface of the snow and exposed to predators as they dash across the snow.

It's true that these are small cuts to the system, but they add up, and it might be worth bringing them into the conversation.